Cr Andy Foster’s comment over on EyeoftheFish regarding issues of eq preparedness in Wellington highlight, for me at least, something of the difficulties of this particular discussion. It is hard to make productive progress, in terms of developing local policies, when the terms of the debate are so vaguely agreed upon by those engaged within it, let alone trying to bring the paying public along too. This is not to disrespect anything that Cr Foster has to say, I have much respect for his work, and for his willingness to engage constructively in a public forum such as EotF. But I do feel that he raises a number of intriguing issues – and this is just my personal response to one of those.

Cr Foster rightly points out that one of the major losses keenly felt by Christchurchers is the loss of their city’s “sense of place”. Along with the loss of significant heritage and iconic buildings, this is exacerbated by the fact that much of what is left of the most public parts of their former city (i.e. its CBD) are still largely off-limits to the public.

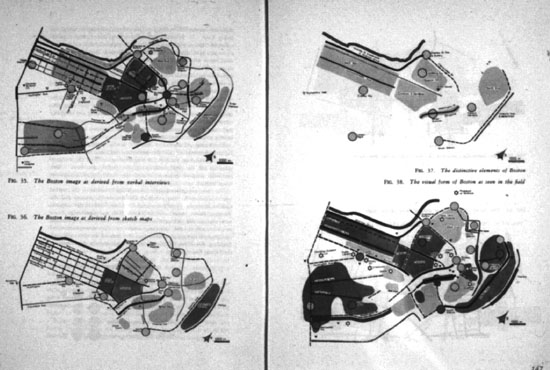

There is a danger, in my humble opinion, when we begin to transfer these ‘learnings’ to other places, without considering the critical differences between those places, and how these fundamentally modify any such ‘learnings’ that might otherwise be applied. Kevin Lynch, rather ineffectually, strived to point this out when everyone else began to apply his 5 elements of legible urban form, with reckless abandon across the urban world: without bothering with the corresponding methodology of public engagement for eliciting them in a place specific way (see Lynch’s 1984 self evaluation of The Image of the City here).

And it is the specifics of place which are key here – obviously – when you are dealing with that notion of “sense of place”.

As I understand it, sense of place is defined by many things – here in Wellington the natural topography/geography especially, as well as climate, culture and history/myth, and our built environment. It should be rather obvious to all that the sense of place of Wellington is vastly different from that of Christchurch – in just about all of the areas listed above, but especially the built environment (which is what I am interested in here). So, if we are prioritising the protection of our sense of place, then policies will need to be vastly different as well. The ‘learnings’, if they are to be productive, are not directly transferable.

Heritage has a role in our perceived sense of place as a part of the built environment – which also includes contemporary buildings, and dare I say ‘iconic’ buildings (old or new) – not to mention all of that developer built dross as well. All of these things contribute, in varying degrees, to a sense of place – some more overtly than others.

While the Christchurch sense of place is (or was?) located deeply within its heritage fabric (and gardens), the same cannot be said of Wellington. In fact, I would suggest that the sense of place of Wellington’s built environment is, by and large, a matter of urban and architectural form rather than the stylistic details of this or that building or era. Think of the curving canyon of Lambton Quay, in which almost any of the buildings could be replaced by one of similar scale and form without unduly altering the general sense of place (except, maybe, the Old BNZ Arcade?). Courtenay Place has its heritage theatres and the Embassy, but the rest is rather unremarkable, and could be replaced again by buildings of similar scale without too much effect on the sense of place. It could even be argued that the Reading complex contributes much more meaningfully to the sense of place in that area than some of the more ‘loved’ older buildings (remembering that sense of place can be negative as well as positive). Newtown’s sense of place, again, is the scale and arrangement, and perhaps also the materiality of its buildings. Perhaps, as much as any particular building, the Newtown sense of place is most significantly informed by its condition – it’s a bit shit after all. The same might also be said of Cuba Street.

OK, so I’m being a deliberatively provocative to make a point, but I really do think that the automatic conflation of sense of place with heritage is an unhelpful one. For every heritage building that is a key part of our sense of place (Wellington Railway Station, St Marys of the Angels perhaps), there are others that might be worthwhile heritage, but make little or no contribution to sense of place (Massey House, Old Saint Pauls). And there are other non-heritage buildings that are key to our sense of place (Majestic Centre, Te Papa).

What I’m trying to suggest is that if eq preparedness means the strengthening of those buildings that contribute most significantly to our sense of place, as Cr Foster suggests, then we cannot simply look to our heritage buildings for this. While that argument might be valid for a city like Christchurch, it is a dead end one here. Instead, we have to accurately assess which elements of our built environment have the most effect on the sense of place that we seek to maintain. In some cases, this might be specific buildings, and some of these heritage ones. But in many, I’d venture, it won’t be. It could be that decent design guides could ensure that the rebuild is such that our sense of place can be retained.

As I’ve already argued here, to properly understand our sense of place, as a collective understanding of this city, then you need to consult the collective: i.e. the public. The fallacy of ‘expert’ definition of its constituent elements is well covered in the Lynch article linked to above. At the same time we should remember that sense of place is not static, and might also productively incorporate our aspirations for the built environment. WCC have made some steps toward this, but it would be really great to see something more comprehensive, engaging its citizens in all of their diversity, to properly understand the place we live in and how it is perceived by us who live in it.

Untangling the notions of ‘heritage’ and ‘sense of place’ is really important. Both are a matter of public value (otherwise there would be no need for public bodies to be involved), but the public value of heritage is much different to that for sense of place (it should be noted that cases where both notions do overlap become points of high significance). That is to say, we need to protect both for different reasons – and because of that, the urgency and manner in which we do this will be different for each case. Understanding this, and its deeper implications, is vital.

Protecting our heritage does not automatically protect our sense of place.

There are other questions of course – the character/heritage area of Thorndon, for example, has its own sense of place. How much does this inform the general sense of place of Wellington? The government precinct has its own complex sense of place in terms of the mixture of heritage buildings – both pre and post war. The MoW generated office blocks ‘behind’ the Beehive (e.g. create a strong sense of place in this area, yet the buildings are fundamentally flawed from environmental and ‘habitational’ points of view – yet they are real heritage (even if not formally recognised), and are a strong contributor to our sense of place, albeit probably perceived as a negative one. Must they be retained at significant cost to the ratepayer – who are probably deeply out of love with them?

We do need this discussion – of how to best protect our city from the worst effects of a major earthquake. We need it to be loud, robust, inclusive, confrontational, reflective, passionate, logical, diverse, informed, sympathetic, considered, interrogative, emotional, and all the rest. Most of all, we just need to have it.

Leave a Reply