What:

Ultrawild – An audacious plan to rewild every city on Earth.

Who:

Industrial Designer (graduated from RMIT c. 2002)

Lives between Wellington and Australia and the rest of the world.

(Is it a co-incidence that in Japanese “Mushin” means “when a person’s mind is free from thoughts of anger, fear, or ego during combat or everyday life” – a Buddhist (Zen) ideal?)

Where:

The Children’s Book Shop (Kilbirnie), Unity Books (City), Schrödinger’s Books (Petone)

When:

Released in October 2023 by Allen & Unwin publishers.

How:

A storm of imaginative ideas drawn, diagrammed and designed, as a beautiful large format picture-book, though it might be better described as a graphic-novelette or dissertation.

Why:

A platform for Mushin to shake people out of their do-nothing, its-too-late pessimism around the future.

Reflection:

Climate change, sea-level rise, the exponential rise in fossil fuel prices, the plateauing of global human population growth and the forecast collapse of species diversity can look like unresolvable ‘wicked problems’ from which the future will only ever be a grim dystopia in the shape of ‘Mad Max‘ or perhaps ‘The Road.’

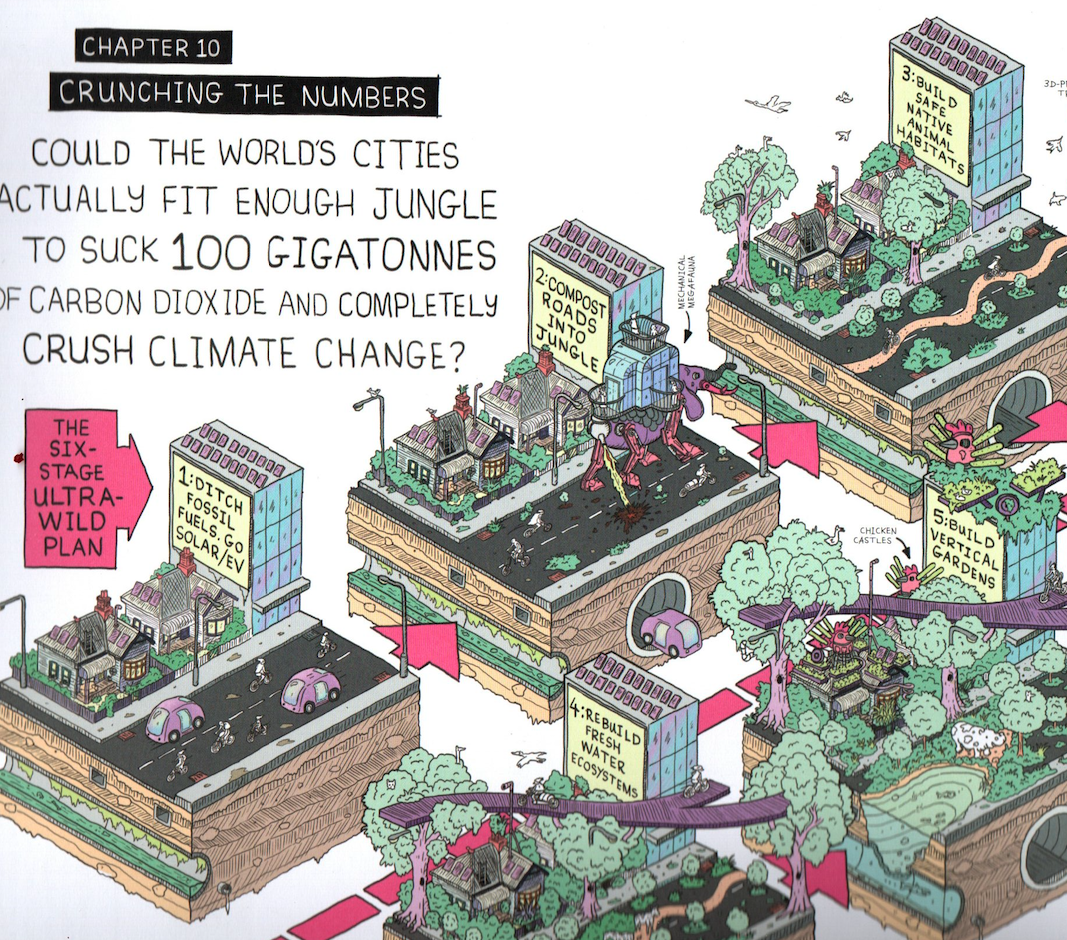

But Mushin is here to show, lead and inspire us to see this future differently – that is, if we choose to. Developing the concept of ‘rewilding’ Mushin presents us with a series of possible, possibly wacky, and out right fantastical inventions that could mean the future is better than the present.

The ‘rewilding’ movement feels like it kicked off in the late 1990s with the realisation that since re-introducing Grey Wolves to Yellowstone National Park in 1995 there had been a dramatic improvement in the bio-diversity of that river catchment area. The science tells us that by hunting Elk, the wolves created a cascade effect where reduced grazing of the river edges (by Elk) then allowed trees to return, resulting in improved filtering of water as it flowed into rivers. This of course (as we are all aware with the call for riparian planting across farms in Aotearoa) improved water quality – leading to a resurgence of fish life. The knock on effects of re-balancing an ecosystem by ensuring the presence of the ‘apex predator’ is not rocket science, but the speed with which change was brought about did seem to take everyone by surprise.

Mushin’s suggestion, one that we in architecture are also aware of, is that greening-the-city will lead not only to a sequestration of carbon (in the form of wood) but will also increase biodiversity of species within the built environment, most importantly in the soil.

If you have not already been told – the best place to store carbon is not in trees, but in the ground itself. None of this is new news, its just that the story of dirt is not very exciting (compared to low-carbon concrete, carbon absorbing concrete, or some other miraculous and as yet un-proven use of concrete that may have some impact on reducing atmospheric carbon at some time in our future).

The additional benefit of soil based carbon (otherwise known as soil-with-high-organic-content) is that is sucks up water and holds onto it like topsie! So if you’ve got a site with surface water ponding the answer is not to pour more concrete on it, but to fill that soil with compost, and then cover it with plants. It you end up with mosquitos get some frogs or a fish or bats (yes we have those here they’re just too clever to be seen much uptil now).

Another facet of the rewilding discourse going around is in economics and social theory. Mushin doesn’t attempt to go there in Ultrawild, but I breezed through Jeremy Rifkin’s ‘The age of resilience : reimagining existence on a rewilding earth‘ (2022) to get some context. Rifkin’s argument is that the economic paradigm of ‘efficiency’ has, like petrol, had its day. We saw it through COVID, we feel it in the health sector, and in construction it is writ large in the recent admission of vulnerability within Fletcher Building. Too much efficiency means there is no slack in the system for when something changes, like interest rates. Rifkin uses natural ecosystems as a model (ironic really given that ‘efficiency economics’ also touted a ‘natural model’ in the theory of Darwinism… but anyway) to suggest that resilience requires slack, lee-way, tolerance etc to give enough room for adaptation. Which brings to mind Maurice K. Smith’s idea of ‘slack’ and the possibilities for the “consistent incompletion of geometry” in architecture (more on that from Mark Jarzombek).

Rifkin has been criticised for not being “on point” and I imagine the same will be said of Mushin – that he is being fanciful and frivolous in the face of catastrophe. What these theorist do recognise however, I suggest, is that solving our ‘wicked problems’ is not a matter of finding a new technology that will save us (eg. maglev vacuum-tube high speed trains… thanks Musk), but choosing to get over the juvenile attitudes that we are maintaining, as if some celestial mum & dad are waiting in the heavens to clean up our mess (eg. “Geez… you were getting told how long you’re allowed to stay in the shower.”)

Leave a Reply