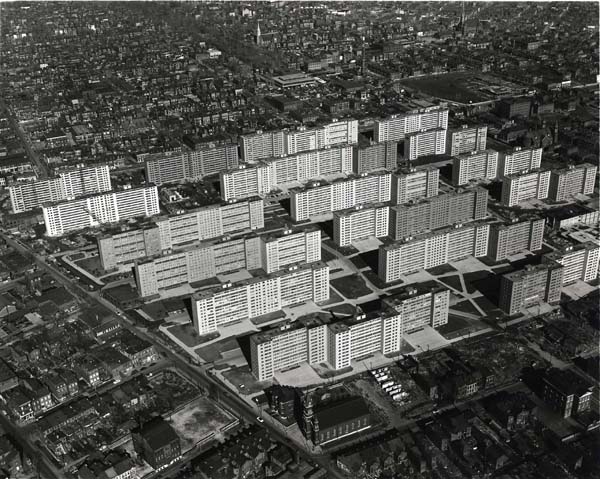

They say that you never forget where you were, or what you were doing, when a major event happens – Man Walking on the Moon, John F Kennedy’s assassination, the destruction of the Twin Towers, or the All Blacks winning the World Cup (in the case of myself, and I suspect many of us, it is: in school, out of school, in a flat in Mt Vic, and in front of a tv). In a similar manner, there are times marked by significant events – the one that springs to mind is the declaration of the End of the Modern Movement, with the demolition of the AIA Award-winning housing project at Pruitt Igoe, on March 16, 1972.

“Upon completion in 1956, the project won design awards from the American Institute of Architects which assessed the project as being an exemplar for future low cost housing projects. But the high-rise design was soon considered uninhabitable by its residents. Parents could not supervise children in the ground level playground, the facilities were inadequate, and the building’s segregation inhibited natural social flows and broke the resident’s established social relationships, allowing crime and vandalism to flourish. Just sixteen years after the initial flurry of accolades, the complex was demolished with almost universal blessing.”

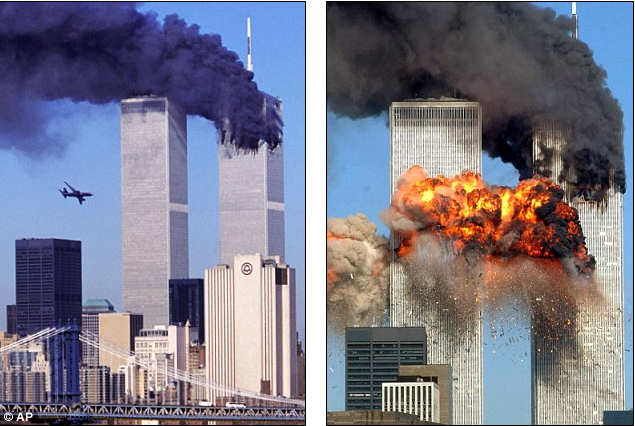

Charles Jencks was fond of pronouncing the announcement of major architectural movements, classifying Post Modernism, announcing the various -isms that have come in and out of favour over the last 30 years. The demolition of Yamasaki’s scheme at Pruitt Igoe must have been a major blow to Minoru Yamasaki, and the destruction of the Twin Trade Towers even more so – how much harder can it get for an award winning architect?!

Post-script comment: Minoru Yamasaki died in 1986, and so did not see the collapse of the World Trade Centre, although his practice would have seen the destruction: they continued on after him, and the practice eventually closed its doors at the end of 2009.

But I think I have another moment for Mr Jencks, if he is still doing his cataloging of architectural trends to the world. This Christmas, just as the rain was gently falling across the entire country, they demolished the AMP building in Napier. Yes, we all know that PoMo is long dead – so firmly dead that they nailed the coffin shut quite some time ago. It’s so uncool to even say you like PoMo, that soon trendy hipsters will be saying they’re keen just because everyone is is not. But the AMP building in Napier, built by the suitably named Hogg brothers back in about 1988, was always the height of ghastly. Its extraordinary facade, Mock Deco to the max, was so crudely designed that it seemed to have been drawn with a blunt crayon on a piece of graph paper. The architects, whoever they were, should remain nameless – actually, they should be named and shamed really, but I suspect that no one is willing to own up to it.

So: 25 December 2010, for me, was the day that Post-Modernism really died. The building, like Pruitt-Igoe, had many years of structural productive life in it yet, but was just so disliked, and badly designed in the first place, that no-one is shedding a tear. Clad exclusively in fibre-cement board cladding, with mock ‘Art-Deco style’ appendages, the building was originally going to go to 8 stories high (permitable at that stage under the Napier District Plan). Luckily for Napier, now widely acknowledged as something of a gem, in its collection of genuine Art Deco buildings, a group called the Art Deco Trust stopped the additional 6 floors dead in their tracks, and it sat, stumpy, for many years. The AMP is dying a well-deserved death – now just a giant pile of rubble on the foreshore. Yes, it is going to be rebuilt, as a Farmers department store, and no, that’s not a perfect solution, but it is better than what was there. We hope.

The big question for me, is that at some stage PoMo will pass the age barrier of permissable nostalgia, and some advocates, somewhere, will call for the ‘saving’ of some classic PoMo buildings. They are, after all, around 30 years old, and so could already be thought of as tomorrow’s heritage…. If you had a choice, what choice piece of Post Modernism would you save, and why?

Leave a Reply