Riding my bike into work this morning, the regular squeeze between car and kerb was suggesting immaterialisation would be my only option. Bloody SUVs. Why do they make cars so wide these days? Easy you say – because we are wider.

Apparently there has been “a gradient of increasing waist circumference over the three periods of 1960–1962, 1988–1994 and 1999–2000 in both men and women. In men, the average waist circumferences were 89, 95 and 99 cm for 1960–1962, 1988–1994 and 1999–2000, respectively [i.e. a 111% increase]. The corresponding values in women were 77, 92 and 94 cm, respectively [a 122% increase].” So let’s see what the comparative automotive obesity increase has been by comparing the randomly selected 1959 mini with a more recent SUV.

The 2009 Honda Pilot measures 190.9″ (length), 71″ (h), 78.5″ (w); in metric that’s 4848.86mm x 1803.4mm x 1993.9mm.

The 1959 Morris Mini 850/Austin Seven measures a comparatively diminutive 10′ 0.25″ (l), 4′ 7.5″ (w) 4′ 5.0″ (ht); i.e. 3054.35mm x 1409.7mm x 1346.2mm. No doubt a completely unreliable comparison between the nippy mini of 1959 and the voluptous 2009 pilot, but even still the number crunching gives an impressive increase of automotive girth of a grand 141%.

The cute little 1959 mini seems to be exactly what our windy little Wellington roads were made for. I’m thinking in particular of the likes of Devon St (a personal favourite), Connaught St, and others typical of our hill-rich inner suburbs, where the idea of two-way traffic presents a daily challenge.

Nostalgia aside, we are clearly well into the era of fat cars, and the need either wider roads or thinner cars, or maybe even less of them. Who was it who said that building more roads to reduce traffic congestion was like loosening your belt in order to lose weight? No doubt road widening comes under the same logic – but one hard to stomach as your inners risk being squeezed out of you on your daily bike ride into work.

But all this thinking of belts and waistlines only got me thinking more about food and architecture, and food and design. The obvious buildings are literally formalist imitations of food, mostly, it seems, vegetables and fruit (like gerkins and pineapples); building versions of New Zealand’s provincial kitsch town icons, which include both food and beverages: Te Puke’s giant kiwifruit, Ohakune’s giant carrot, Gore’s brown trout, Riverton’s paua shell, Kaikoura’s Crayfish, and of course the world-famous-in-NZ Paeroa L&P bottle. I’m waiting for the Kahurangi cupcake to arrive on the scene.

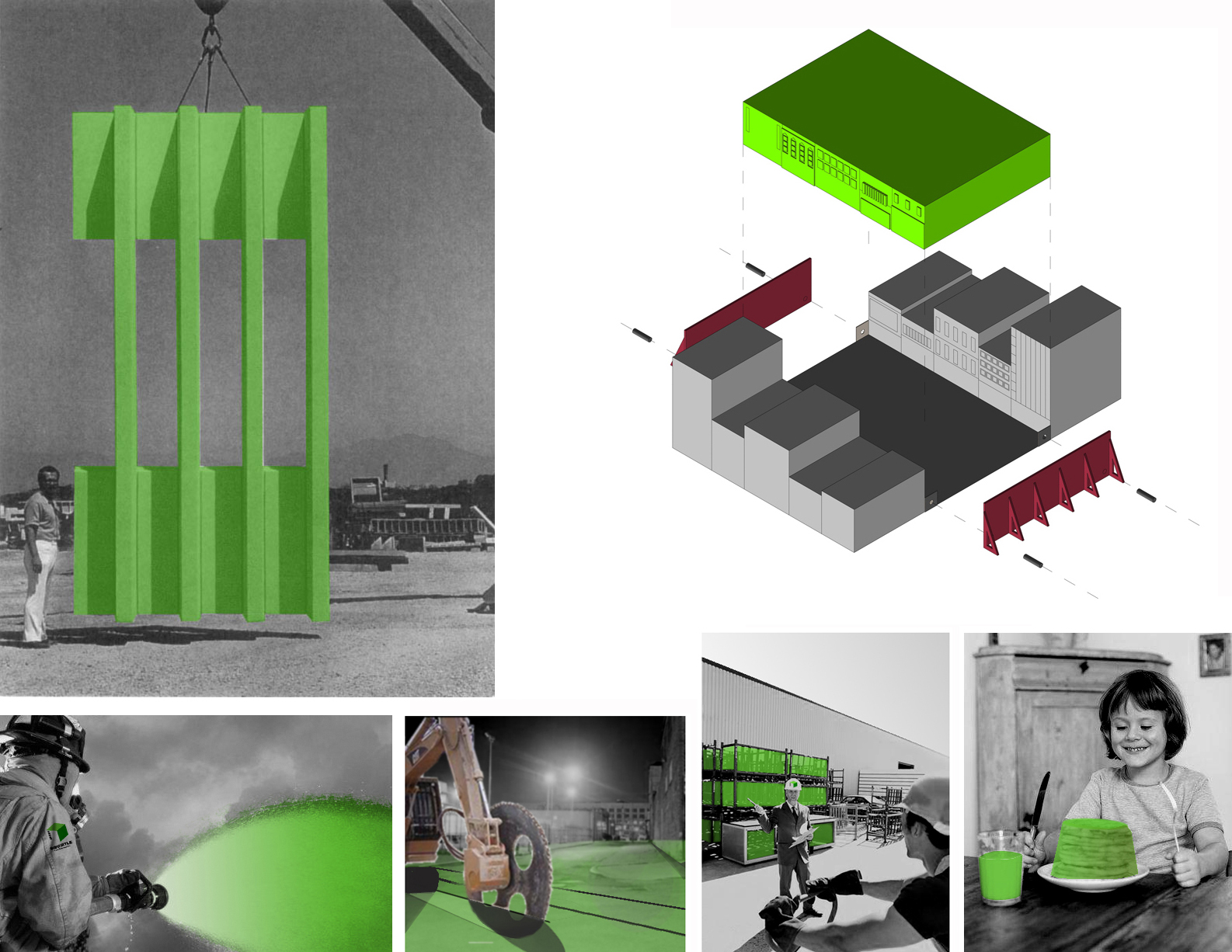

But more fascinating projects productively take food and architecture into perversion. A perfect example was one of the winning entries from the 2005 20under40 competition, where the entrants (G10: “Squirtle Food Industries Ltd” Rob Bark, Rhys Williams, Jamie Roberts, Linda Bierl, and Danika Grandkoski) proposed growing and then eating architecture in response to the 20u40-brief where Wellington’s road had become privatised and available as building sites.

Food, or at least food processing has, if Lupton and Miller in The Bathroom: the Kitchen: and the Aesthetics of Waste are right, even impacted on some of the most significant design movements of the twentieth-century. They argue that parallels existed between commercialism’s planned obsolescence and the imagery of biological digestion, which influenced on early C20th design. As they put it:

“By the phrase process of elimination we refer to the overlapping patterns of biological digestion, economic consumption, and aesthetic simplication. The streamlined style of modern design, which served the new ideals of bodily hygiene and the manufacturing policy of planned obsolences, emanated from the domestic landscape of the bathroom and kitchen.” (p. 1)

Another of my favourite books on the topic of food and design is the Catterall-edited Food: Design and Culture. Firstly it has fantastic photographs, which are luscious and often perverse.

Secondly it’s quite upfront about the cultural and artificial production and design of food, and NZ gets it’s own special mention via the kiwifruit:

“Twenty-five years ago the kiwi fruit was a genuine exotic. … Moved by government subsidies rather than any very elevated gastronomic initiative, New Zealand farmers started culivating the kiwifruit and successfully promoting it as a valuable source of vitamin C. … Suddenly, slices of kiwi were everywhere: a sloppy shorthand for “sophistication.” Kiwi became garni, … [but] Its presence in the limelight of sophistication was a very brief one … To serve a kiwifruit today in any form would be brazenly to declare one’s naivete or gullibility, one’s complete ignorance of fashion … or, you might say, to declare one’s resistance to fashion and one’s brave and independent spirit. It is at this point that the kiwi may yet be ready for an ironic revival” (Stephen Bayley “Food as fashion” p. 36); something no doubt the citizens of Te Puke are keenly aware of.

But wait there’s more. Not just food and architecture, but food and crime.

A week or so ago I heard a fascinating programme on National Radio’s weekday Night’s programme attributing crime to diet. I can’t find evidence of it on their website – it may have been in the catch-all basket of “Windows on the World,” or perhaps I dreamed it – a mad idea that food might impact that significantly on behaviour. But no! A little web-searching and it seems to be true. Some people think food causes crime, and an experimental trial is taking place to prove or disprove this. The implications for social policy, supermarket regulations, school tuckshops, prison dinners, and TV advertising will be phenomenal. I can’t wait to see what the National Party pass through on urgency with this as ammunition, and of course, I’m utterly confident that car-thinning legislation will also be on the agenda. The cyclists of the world wait with bated breath.

So maybe food, nutrition, call it what you will, but maybe it is the answer to everything.

References

Claire Catterall (ed.) Food: Design and Culture (London: Laurence King, 1999)

Ellen Lupton and J. Abbott Miller The Bathroom: the Kitchen: and the Aesthetics of Waste: A Process of Elimination (Cambride, Massachusetts: MIT List Visual Arts Center, 1992)

Leave a Reply