As I have not had much of a chance to spend time with many of my favourite Modernist projects of all time … starting with Kahn’s in Rochester, Lewerentz’s in Klippan, Scarpa’s in Palermo and Breuer’s in Collegeville … it seems only right to choose a project I’ve known well for decades and fits within a cultural context I’m totally sure was a wonderful phase of all the different Modernisms: Viljo Revell’s Toronto City Hall (competition 1958, completed 1965).

Toronto in the 60s and 70s (even though few of us hypercritical students would admit it at the time) was building some exceptional Modernist projects. There were years when Mies’s unveiled his biggest and possibly best ensemble of towers and pavilion, an elegant steel IM Pei tower and could shop or eat in superb interiors by Finn Juhl and Janis Kravis. We all had design tutors who were German, Estonian, Norwegian or had worked at Aalto’s or Corb’s and were doing projects in Iceland or Holland. We sat on Artek drafting stools, Relling armchairs, wore Marimekko and bought Dansk, Georg Jensen, Orrefors and Holmegaard. Were we steeped in Scandinavian/Nordic design culture.

For me I think this began in the spring of 1965, when as an eleven year old on my bike exploring the city, I chanced upon a house under construction where two cranes were holding a clump of mature elms in situ while an excavator worked on an underground garage. I followed the work there for more than a year as the house was poured-in-place. On this exclusive cul-de-sac of fully-frontal Neo-Georgian brick houses I loved the asymmetry, flat roof, panoramic glazing taking in the curve of the street’s topography and the board-formed walls extending out to half-enclose the courtyard and into the interior.

My untutored instinct, as it turned out, wasn’t all that bad: 95 Ardwold Gate was designed by Taivo Kapsi, an Estonian-Canadian architect who had, since 1961, been working with Viljo Revell’s Helsinki design team on their 1958 international competition-winning Toronto City Hall (TCH).

As a family we went downtown to the opening of the TCH that autumn and had a position on Revell’s raised terrace colonnade which defines City Hall Square (CHS) on the bigger urban block. This framing device is a screen from the busy surrounding streets but open enough not to separate the 5 ha city hall precinct from the immediate area. Later my design tutors told me how Aalto would have shown Revell, who for a time worked for Aalto, how to raise and separate the public spaces of urban projects above and away from car noise and fumes. The drama of Revell’s design for CHS as a monumental forecourt is its potential for civic-sized gatherings, celebrations, and protests as well as a place in the sun and shade and with places to linger. For many though CHS is all about the ice rink under Revell’s arches. It is as open, generous, dramatic and comfortable a Modernist urban stage as any I know. Skating at CHS trumps The Rockerfeller Center experience largely because of the careful asymmetrical placement of the pool/rink on the reticulated podium which is within the concrete frame of the colonades and of course the elegance and small scale of the building ensemble it forefronts.

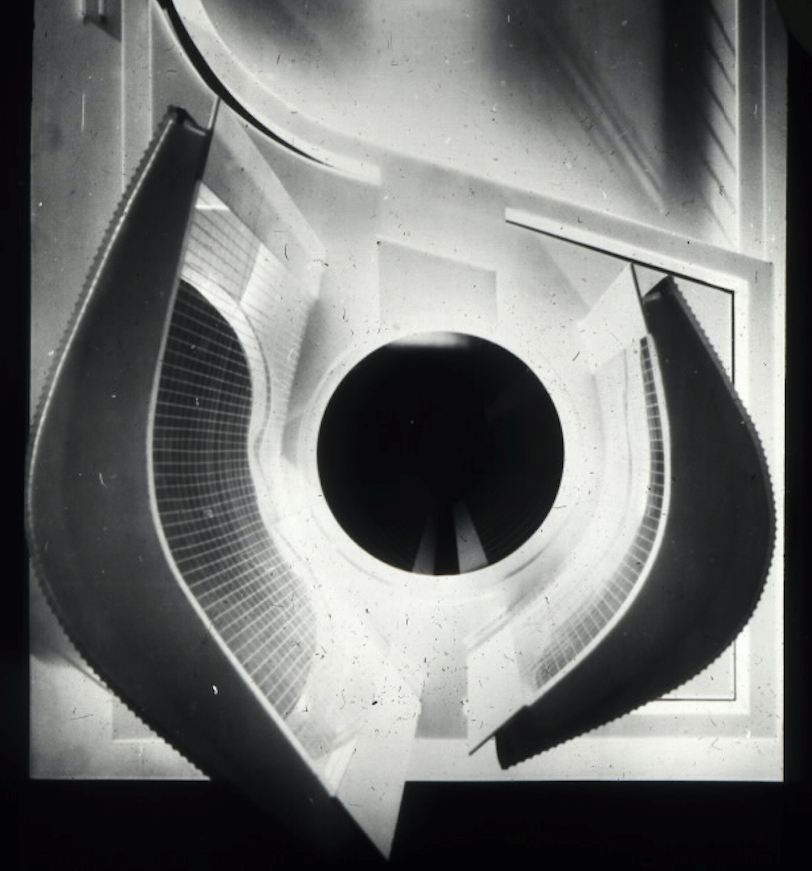

From City Hall Square one approaches the Toronto City Hall through its wide a publicly accessible foyer podium structure into which is embedded the council chamber and out of which rise a pair of municipal office towers. Revell’s ensemble is an exceptional architectural idea with symbolic clarity: specular transparency within unfenestrated marble and concrete shells. I would say now that it’s in a good way that the TCH itself turns its back to the surrounding context of historic old city hall and law school and courthouse, large department stores, office buildings and hotels. The towers turn their back to the sides and back of the site because it is opening itself to those in the square and those approaching it.

For me the TCH is also partially a figment as much of Revell’s innovative structural design (like Utzon’s 1957 competition project for Sydney) was lost to economies at the developed design stages in conjunction with John B Parkin Associates Toronto. Revell’s office floors were to be cantilevered off a wide and deep vertical truss on embedded in the thickness of the back of both towers, and each office floor level was articulated as three office terraces stepping down in section to the uninterrupted curved glass walls facing each other across the central void of the tower levels. Revell would have known of this sectional idea from Jørn Utzon’s unpremiated 1953 Copenhagen Langelinie Pavillionen competition project.

Even if the municipal budget was not made to stretch as far as it could have, and some aspects of its conception, planning and detailing are a disappointment in its realisation the Toronto City Hall demonstrates the achievement of Scandinavian Modernist sensibilities in playing up the pleasures of formal and material exploration.

Michael Milojevic

The “My favourite modernist building …” series is in support of Gordon Wilson Flats which is facing threat of demolition.

Leave a Reply