Too soon for bad-taste comments? Sorry Michael – I never knew you at all, but with a name like Graves you’ve probably had those jokes all your life. A life which has just ended – yes, sadly, the world’s greatest Post-Modern architect has, like the architectural style that he helped spawn, passed away. Far be it for the Arch Centre website to become just a succession of obituaries, but it is worth spending some time on the man, the movement, and the fusion of design craziness that they created together.

If you want to know more about the man, the Architectural Record has a good obituary here, which tells us he died at home in Princeton, aged 80, and was best known for two things: the Portland building in Oregon, and the whistling kettle he created for Alessi. Both were hugely iconic and defined a generation, but both were fundamentally flawed in basic functional design principles. The Portland building was undertaken by Graves when he was in his early 40s and had never built anything that size: a giant cube of space decorated on the outside with stripes and even large floral decorative wreathes, it has had endless discussion over its suitability as an office, it’s structural stability and weathertightness, and has recently been proposed to be demolished. Perhaps it already has been.

“Yet the construction problems are only one part of the Portland Building’s sadness. Graves’ original, garland-festooned confection was value-engineered to a graphic study of color and pattern. The interior is a miserable place to work: the tiny windows yield little natural light (Johnson’s Arab-Oil-Embargo-era competition prized energy efficiency which, with the technology of the time, was a building with no windows.) And then there’s the building’s urban design: city officials wanted the main entrance to face the then-new transit mall, but ironically, still wanted parking in the building for themselves — thus, a cavernous garage door faces a city park. As one architecture critic wryly put it: “Where you expect dignity, you get the building’s anus.”

The whistling kettle, a whimsical piece of stainless steel design for a kettle you actually place on the hob (I know – who even does that any more!) had a sweet little bird that whistled when the water boiled, but few people used the kettles, as to pull the bird out of the spout when wanting to pour a cup of tea, risked scalding hot steam taking the skin off your fingers, and the gleaming kettle getting dirty. Many people had one – few used them more than once or twice. That didn’t stop people buying them though: Alessi sold millions.

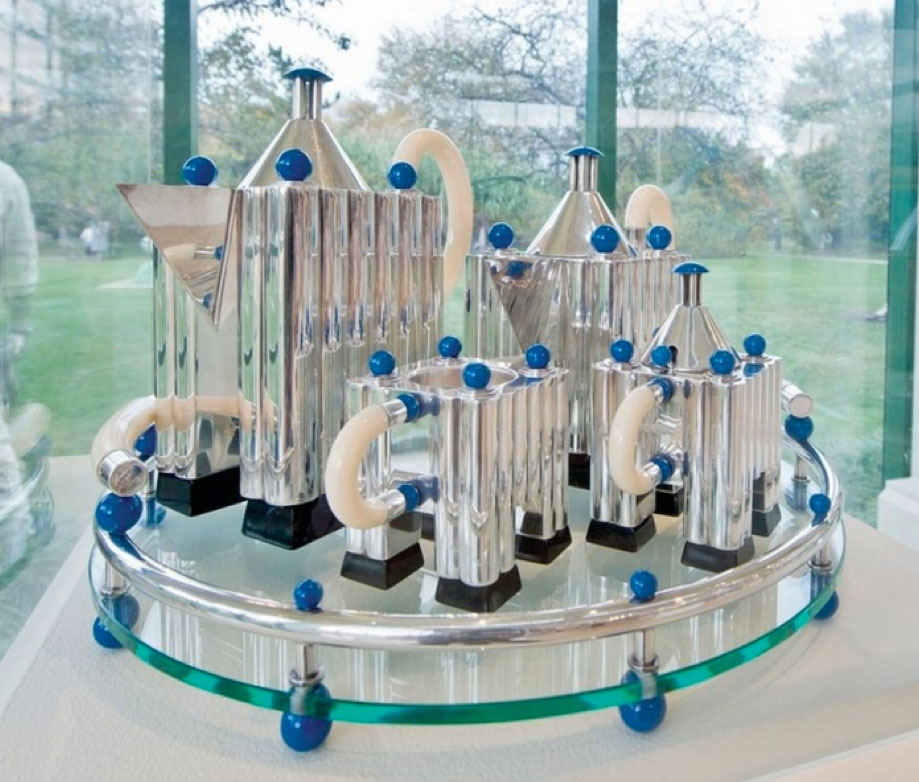

A triumph of design and looks over functionality? Don’t let it stop you: over the years, Graves and his company went on to design thousands of cute PoMo goodies for Alessi and for Target: over 2500, apparently. Surely not all of them were crap? You may notice, from the picture below (taken at a 2014 retrospective of Graves’ product design work for Alessi and Target) that the same kettle still features, albeit now with an electric cord, and without a whistling bird…

Michael Graves did not start out as a Post-Modern architect though. In fact, his early years were as part of the New York Five, a “group” of hot young designers all keen on creating orthogonal, crisp, white designs in strictly functional modern capturings of space.

Some of the Five still continue to do so: Eisenman has never got over himself, and still designs white on white grids of space. Time to move on Peter! Graves, by comparison, was quick to hop on, and via Philip Johnson’s direction, even lead the bandwagon of PoMo architecture that joyously referenced back to the classical, or neo-classical periods, as well as Regency, French colonial, Mickey Mouse, and whatever else took his fancy.

Post-Modernism gave Graves the freedom to move, create chaos, and actually laugh at the world – laugh at himself, laugh at the stuck-up Modernists with their stiff white cubes (yes Peter, we’re talking about you!), and laugh along with you and I at the whimsy of a singing bird kettle that whistled at you when the jug had boiled.

Personally, I loved the Humana building in Louisville Kentucky, a spiritual sister to the Portland building, and sometimes mistaken for it in detail shots – but actually very different. The Humana building was tall, and almost elegant, instead of squat and awkward. The Humana building, 26 storeys tall and showing off every inch of the way, features a perching portico near the top, an echo of the bird-houses that Graves was also designing around the time. Scale is flexible. Is that a model for a birdbath, or a model of a house?

Is that a tea-set or an office park? Go on, have a look at it. What’s good for the goose, after all, is well worth a gander.

So, farewell Mr Graves, and thanks for all the fish. As a harbinger of PoMo in all its glory and its madness, you influenced a generation of architects in New Zealand as well as in America. Athfield, our most eclectic of architects, went through a staunchly PoMo phase as well, with the gloriously wacky Church of Christ the Scientist being perhaps his most out there PoMo design. Graves never came to New Zealand (famously, neither did Eisenman…), but your legacy will live on here too, for a few more years yet, until the thin 1980s cladding systems fail and they return to dust here as well, taking their secrets to the graves…

Leave a Reply