I haven’t been down to the container exhibition of WCC’s Wellington 2040 vision, but am looking forward to doing so soon. What I have seen is the recent post over on EyeoftheFish, which gives us a sneak preview of a small part of the type of outcome that might be expected to emerge from that vision: in this case, a new green space where the Oaks building is currently sited. As the Fish reports, that site has been the subject of many suggestions for ‘improvement,’ some of which are captured in this thread. A particularly intriguing one was the suggestion of a ‘Flatiron’/wedge-shaped building on Te Aro Park, and a park where Oaks currently is – a swap of building for open space and vice versa.

Anyway, WCC’s artist’s impression for this specific site (in accordance with the 2040 vision), has been published by the Fish, which I have plagiarised (above) for this post (click on the image to see it larger over on EotF). Although WCC might well be congratulated for a bold vision and a positive intervention in our urban fabric, at a detailed level, the featureless expanse of lawn probably leaves a lot to desire (and would present a heck of a maintenance issue, even worse that those that currently exist on the Te Aro Park part of the site). That aside, there are other, I think more interesting, issues here that seem always to be overlooked when discussion of what to do with Te Aro Park arises – in particular, issues of both urban and cultural heritage.

Te Aro Park is deeply unloved by most commentators and general public alike*. It doesn’t fit our idea of what a contemporary ‘Western’ urban space should look like – all tidy with sharply delineated edges and slick public furniture (i.e. the ‘Wraightian’ sense), or, on the other hand, in the softly moulded and more ‘naturalistic’ micro-Picturesque format (which is so out of fashion with designers, but still, I suspect, very popular with our public). Instead we have untidiness of detail (exacerbated by a poor maintenance regime and other factors), and an indeterminacy of function due to a design language that is quite ‘other’ to our expectations – those triangular seat/benches for example, or the use of pottery in various forms as one of the key materials at the site, or the shifting/weaving geometries perhaps, and so on…

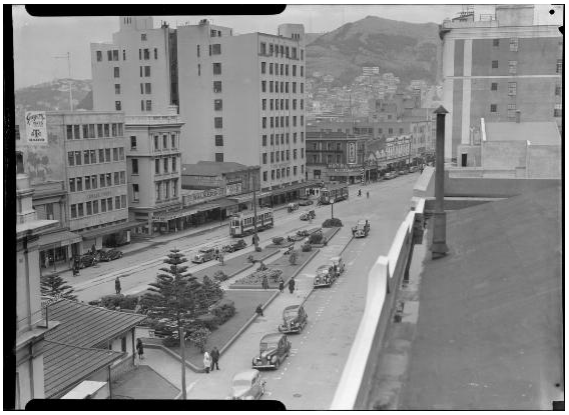

The park was of course, very contentious from the outset, and is much more famous (or infamous perhaps), for this reason than for its design. Shona Rapira-Davies became a much targeted figure during its construction, not only for her inability to manage the project according to her contracted obligations, but also for her somewhat abrasive responses to these criticisms. Considerable budget and time overruns for an indulgent project (such as this turned out to be), are never going to be popular with the rate-paying public, and even less so when the park is delivering something unexpectedly other on a site that was much admired in its previous form:

WCC had bold and enlightened plans when they commissioned Rapira-Davies to design and construct the park. The intention was to create an artwork at the scale of urban intervention – art that was not just a single object “plonked in space” (ala Sculpture Trust), but an integrated work of both art and urban fabric. They were excited at the prospect of creating the largest artwork in New Zealand.

Rapira-Davies’ proposal must also have been attractive insofar as it connected explicitly to the pre-European history of the site. her proposal addressed themes and issues of Maori culture and history – and from Rapira-Davies’ stance on Maori Feminism (the entwined nature of the Maori rights movement and the Feminist movement of the 1970s is an interesting area of study…).

The park itself sits on (or very near) the former pa that existed on the site. Rapira-Davies’ scheme was in fact a subversive move (although also an endorsed subversive move), to symbolically reinstate the former pa – “to force recognition of its shifting histories and cultural usages” (so writes art historian Jenny Harper). If the language and design moves are somewhat other, then this recognises the need to react against the existing built environment, and to replace it with ‘natural’ forms (e.g. the native trees that never flourished, flowing water pools that evoke a former stream, traces of plants impressed into the tiles before firing, etc), as well as traditional Maori cultural motifs, such as the interweaving geometries, the tukutuku inspired patterns of the glazing etc, the evidence of handwork deliberately left as traces in the tiles as an echo of the closeness of the hand to Maori craft, and so forth.

It is not supposed to be a ‘comfortable’ space for the contemporary New Zealander – it was not designed to be easily accessible.

And, of course, therein lies both the power of the space and its undoing. Further examples: you may have noticed the Maori names on the tiles of the ‘bridge’ between the waterfalls – these are the names of vanquished ancestors – now walked over daily as further insult to their mana. You may also be able to detect the figures depicted in the pool tiles’ coloured glazing – 3 depictions of a goddess/guardian figure as: a young girl, an adult, and an elderly woman (these were ‘painted’ by Kura te Waru Rewiri). The trees along the street edges are the warriors powering the canoe that the general shape of the site represents – the prow being the obvious element at the Taranaki Street end. These vertical elements are the ‘male’ presence of the site, with the ‘female’ element represented in the more dominant and elaborate horizontal plane. The park is extraordinarily rich in symbolic readings such as these – on a level that is far beyond any contemporary project I can think of – too much for most of us to contemplate perhaps.

Check out the panorama of Te Aro Park supplied by Panoramic Earth

Despite all these words, I’m not advocating for the retention of the park. I am arguing that it has significant heritage value (in terms of Wellington’s cultural, social, and urban history), but that in itself, for me at least, doesn’t mean that it should be kept – although I am impressed that other more ardently ‘pro-heritage’ commentators can easily dismiss something of this nature. The issue of whether the park should be kept as heritage, in the face of its unpopularity (when heritage suggests inheritable value) is fraught, and I’m all in favour of a decent urban fabric and public environment. But it seems to me that the full debate is not being had, and that (to me at least), is rather problemmatic. This post, then, is my attempt to ‘table’ some broader material for such debate.

Whatever. It’s all too late of course – the park is due for a light upgrade next month (2040 vision notwithstanding). The triangular seating is a key target apparently. Oh well – what we didn’t even realise that we had, probably won’t be missed…

To be completely honest, this post actually began as a brief Video of the Week entry for your Friday entertainment needs, but it kind of got away on me. The video that I was going to feature is “Cat Among the Pigeons” – featured in 6 parts on the NZ on Screen. It is a great historical documentary that covers the construction period of the park – capturing well the work that Rapira-Davies put into it, and balancing her aggrieved point of view nicely with the attempts of the key WCC players to be as accommodating to her as possible, whilst still trying to achieve a positive outcome in the face of strident public opposition… It’s well worth the watch:

You’ll have to watch the doco to see where the title of this post comes from…

* I’m quite intrigued by how popular the park is (especially compared with the newish Courtenay pocket park across Taranaki), on a good day – but that may be more representative of the lack of public open space along our golden mile than any evidence of a popular appreciation for its urban design qualities…

Leave a Reply